Race, Identity, and Actualization

Hold the Line

Joan was tough, or so her sister said. But holding my hand, she melted. We held a colorful love between us that joined generations, cultures, and religions. A timeless love, in which I was a son, a brother, a father. Forty years ago, her father sent her into a civil upheaval that had split churches, bombed schools, and uprooted families. Nashville had dragged it's feet on integration over the course of 15 years since Brown v. Board of Education, and finally succumbed in 1971 to a court order. Joan was in the first senior class to be desegregated.

Many black students quietly accepted their fate. Their parents encouraged them to be quiet, ruthlessly polite, and ignore any flak coming their way. They were making history, and making history is tough. Joan was polite, but not one to stay quiet. So when the white girl in the desk in front of her brushed her hair onto Joan's desk, she immediately said, "Excuse me, if you really need to brush your hair, please brush it to the side of your desk, or onto your own desk, not onto mine." Joan gestured expansively as she told the story, as if to demonstrate her extraordinary clemency. The girl sighed dismissively, and turned around. The next time it happened, she reminded her sternly, "Excuse me, I told you not to brush your hair onto my desk, that's gross. Please stop." Again, she met with dismissal.

The third time it happened, Joan was ready. She had a piece of paper on her desk, and scissors - this was home economics class after all. As the girl brushed, Joan noiselessly cut a chunk of hair off which landed squarely on the paper. Joan wrapped it up neatly, tapped her on the shoulder, and handed it to her. Maybe it was a note from one of her friends? When she opened it, and realized it was her own hair, she started screaming, and never stopped. Both girls were summoned to the principal's office -- but separately, of course. The principal called Joan's parents to admonish her. Joan proudly said her parents answered, "What can we do? She's a tough girl." While he might have ordinarily suspended Joan, he knew that might have caused a race riot. So she got off without any punishment. They seated the two girls separately, and that was the end of that.

Tangled Web

Twenty years later, I wrote a note to my classmate Nadine, proud relation to black poet and activist Nikki Giovanni. We were sitting in Martin Luther King Junior High School, on the site of Pearl High, opened in 1937, which, as Wynn wrote, "eminent authorities considered one of the most modern, best constructed, and well-equipped buildings for Negroes in the South." Across the street was a park that black people could not enter in the segregation era. Pearl had been integrated with the predominantly white Cohn High School in 1983, as Nashville struggled to balance federal mandates, parent's schedules, limited budgets, complicated busing, and continuing, if veiled, resistance to integration. We kids knew little of this history, but it affected us profoundly, often by the things adults left unsaid.

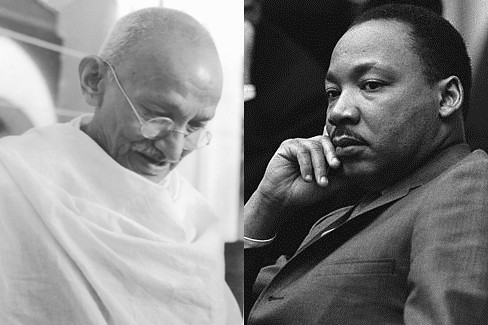

|

| Gandhi and King |

My best friend Julian stole and delivered my note in that delicate moment after you declare your love, before you want to share it. I probably wrote something suave like "Do you like me? Check yes or no." I might have vainly hoped my hair, which black girls complimented, would win her over. In fact, as Chris Rock later taught me, tonnes of hair like mine from one of the holiest temples in India is sold to black women in America every year. Hair weaved together the heads of two brown cultures who's nonviolent resistance had prevailed in a long, uncertain struggle for civil rights.

Born brown into the "We are the World" optimism of the 80s, I believed color blindness was dawning. I attributed the occasional "When are you going back to India?" comment, most ironically at a Rotary Club scholarship banquet, to a dying, even cute, ignorance. I liked lots of girls, black, white, and asian, and didn't feel awkward about it. So I looked hopefully to Nadine when she responded privately to my note, with a maturity a decade ahead of my own. "I respect you and I think you are a great person, but I do not like you romantically."

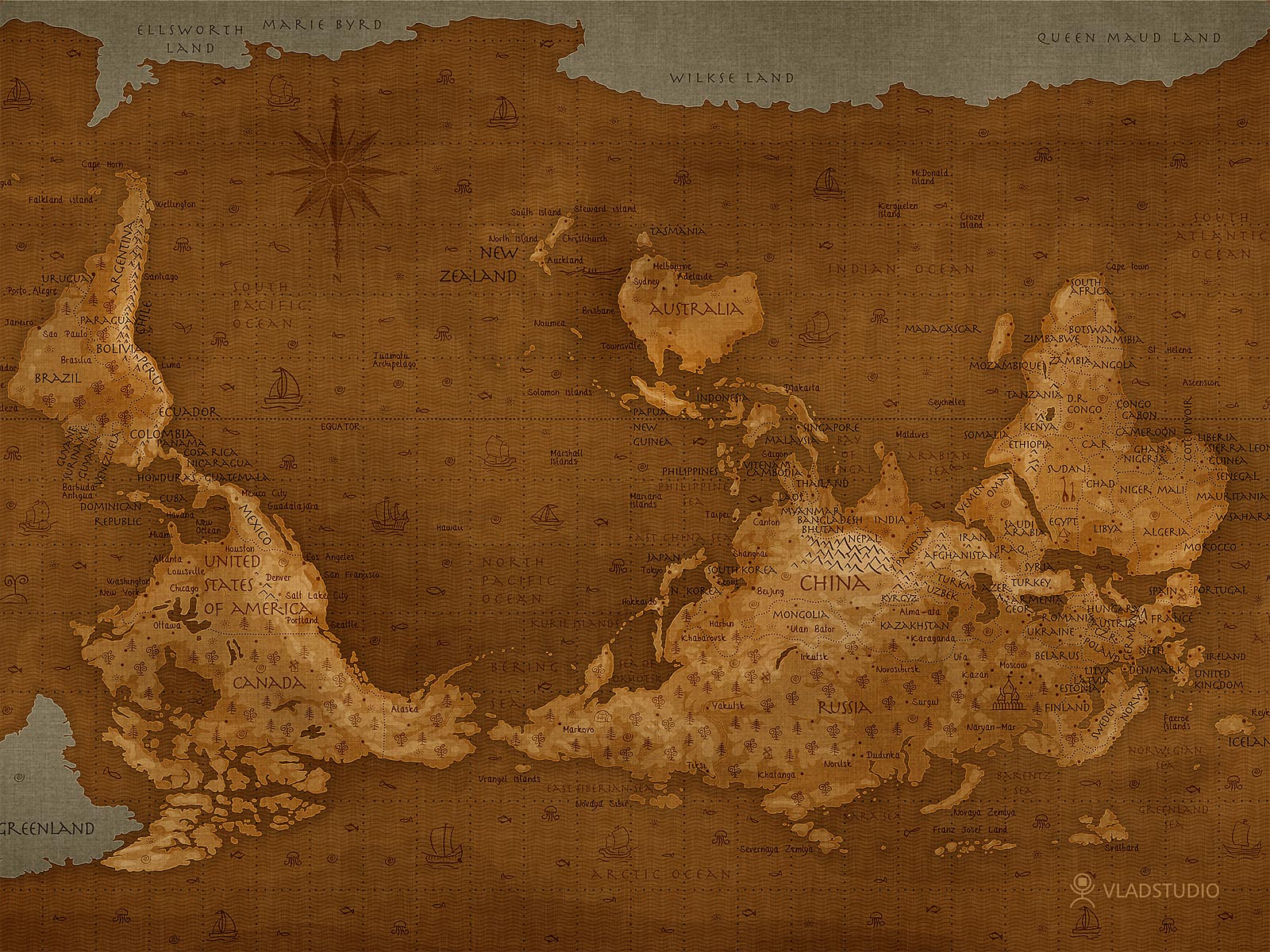

|

| Nashville's lunch counter sit-ins were an early success for nonviolent resistance |

What did I see when I arrived in my freshman high school lunchroom? Did I see what Joan's son Terrence saw? He saw a clear choice between eating with black people everyday or with everyone else. I'd like to think our black-white-brown-asian group accepted him for who he was. But when he sometimes chose us, black people took notice. "What, you think you're too good for us?" they asked him. In choosing freedom to associate, Terrence lost acceptance, and was taunted daily. He asked his mom to let him transfer out of our school, one of the best public schools in Nashville. Joan responded, "I'm not working my butt off night and day to let you slack off at another school. You better learn to like it there."

Struggling to exist in this environment, Terrence developed a legendary "mean girl" attitude. I still have an afterimage of this personality decades later, irreconcilable with the warm, vulnerable Terrence of today. One day after he proudly wore a leather jacket his mother had saved up to buy, he lost it. Heartbroken, it took him a week to figure out that Max, a black classmate had stolen it to prove a point. In those lax days of school management, Joan called Terrence at the principal's office, and made him give the phone to Max. After being yelled at for a while, Max said, "Listen, I was just trying to teach Terrence a lesson." Joan responded, "Well, congratulations, it worked. You have taught him that he doesn't have a friend in this world." History saves room for irony.

Broune Identity

A South Indian in the American South, my skin color bestowed me virtual citizenship in the Global South. Foreigners often give me an unexpected, maybe undeserved empathy. In Cambodia, I was a brother. In Malaysia,

I was fair-skinned, in Turkey I was black. In Tanzania, I was nearly arrested for being a spy of the Indian government, in Mexico or Peru, I tried to pass for indio. In Australia, my brothers found discrimination, in Germany, admiration. Moroccans were disappointed with my limited knowledge of Bollywood. In Britain, I was more native than in America. In India, I could be from America, elsewhere, I could be from India. A South African teen, who had just acted in an anti-apartheid play once asked me, "So you are an Indian Tennessean, but not Cherokee?"

I was fair-skinned, in Turkey I was black. In Tanzania, I was nearly arrested for being a spy of the Indian government, in Mexico or Peru, I tried to pass for indio. In Australia, my brothers found discrimination, in Germany, admiration. Moroccans were disappointed with my limited knowledge of Bollywood. In Britain, I was more native than in America. In India, I could be from America, elsewhere, I could be from India. A South African teen, who had just acted in an anti-apartheid play once asked me, "So you are an Indian Tennessean, but not Cherokee?"

But it's always gratifying to return home and feel unexpected community. As I've grown my hair and beard recently, people start to make comparisons. At the Nashville airport, a particularly smiley security agent said, "Do you know, you look like..?" Interrupting, I said, "Yeah I know, brown Jesus." He responded, "Well, I'd prefer to just say 'Jesus', if you know what I mean."

1 comment:

for a long time, i felt like there were zero places in the world where i could "pass" as a local, where i looked like i fit in. in my white community, i was one of 5 asian kids in a sea of irish, polish, white mutt kids. when i finally visited taiwan, somehow ppl could tell i wasn't from there; plus i still felt like an outsider. it's hard to shake that outsider feeling when you've grown up w/it, even at this point, when i realize there are a few major cities i could live in without anyone asking me "no, where are you *really* from?"

Post a Comment